Category: Criminal Law / Constitutional Law

Reading Time: 12 Minutes

Author: Uttkarsh Bhatt

Edited and Reviewed: Editor Legal Whizz

Introduction

In the history of Indian criminal jurisprudence, few sections have sparked as much debate, controversy, and political friction as Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC)—the colonial-era law on sedition. For over 150 years, this law stood as a sentinel, often accused of stifling dissent under the guise of protecting the state.

However, with the dawn of India’s new criminal justice era marked by the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), 2023, the word “sedition” has officially vanished from the statute books. It has been replaced by Section 152 BNS, which penalizes “acts endangering sovereignty, unity, and integrity of India.”

But does the removal of the word “sedition” mean the offense is dead? Or has it merely shed its colonial skin to emerge in a more potent, modern avatar?

This article provides a comprehensive legal analysis of the transition from Section 124A IPC to Section 152 BNS. We explore the historical context, the key differences in the new law, the constitutional implications for free speech (Article 19), and whether this shift represents true liberation or a “repackaging” of old restrictions.

The Colonial Legacy: Origins of Section 124A IPC

To understand the future of the law, one must revisit its past. The concept of sedition was never about protecting the Indian people; it was about protecting the British Crown from the Indian people.

The Macaulay Draft and the “Oversight”

The origins of sedition law in India date back to the 1830s. Thomas Babington Macaulay, the architect of the IPC, included a clause on sedition in his Draft Penal Code of 1837. Interestingly, when the IPC was enacted in 1860, the section was famously omitted—an event attributed to a legislative “oversight.”

It was not until 1870 that Section 124A was inserted into the IPC by Sir James Fitzjames Stephen. The amendment was a direct response to the increasing Wahhabi activities and the need to curb nationalist sentiments.

The Weapon Against Freedom Fighters

The British Raj utilized Section 124A as its primary weapon to suppress the Indian independence movement.

- Bal Gangadhar Tilak (1897 & 1908): Tilak was famously tried for his writings in Kesari. His trials transformed the courtroom into a political theater, where he famously challenged the legitimacy of colonial law.

- Mahatma Gandhi (1922): In his historic trial, Gandhi famously termed Section 124A as the “prince among the political sections of the Indian Penal Code designed to suppress the liberty of the citizen.”

Despite this oppressive history, the law survived Independence. While the Constituent Assembly debated its validity—with K.M. Munshi successfully arguing to remove the word “sedition” from the Constitution—the section remained in the penal code, creating a paradox in independent India.

Decoding the Old Law: Section 124A IPC

Until July 2024, Section 124A of the IPC defined sedition as follows:

“Whoever, by words… brings or attempts to bring into hatred or contempt, or excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards the Government established by law in India…”

Key Elements of Section 124A

- Disaffection: Explanation 1 defined this as “disloyalty and all feelings of enmity.”

- Target: The offense was against the Government, not necessarily the Nation.

- Punishment: Imprisonment for life, or up to three years, plus a fine.

- The “Tendency” Test: Courts often grappled with whether mere words were enough or if an actual incitement to violence was required.

The vagueness of terms like “disaffection” allowed for broad interpretation, leading to the arrest of cartoonists, journalists, and students for acts ranging from cheering for a rival cricket team to criticizing government policy.

The New Era: Section 152 of Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS)

With the enforcement of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), the IPC has been repealed. The legislature chose not to use the term “sedition.” Instead, it introduced Section 152, titled “Act endangering sovereignty, unity and integrity of India.”

The Text of Section 152 BNS

“Whoever, purposely or knowingly, by words… or by electronic communication or by use of financial means, or otherwise, excites or attempts to excite, secession or armed rebellion or subversive activities, or encourages feelings of separatist activities or endangers sovereignty or unity and integrity of India…”

Major Changes and Additions

The transition from IPC to BNS introduces critical changes:

- Shift from “Government” to “Nation”: While 124A protected the “Government established by law,” Section 152 focuses on the “sovereignty, unity, and integrity of India.” This is a significant conceptual shift from protecting a political entity to protecting the State itself.

- Explicit Mens Rea (Intention): Section 152 uses the words “purposely or knowingly.” This explicitly incorporates mens rea (guilty mind), theoretically raising the threshold for prosecution compared to the older section where intention was often presumed.

- Modern Warfare: Electronic & Financial Means: Recognizing 21st-century threats, the BNS explicitly includes “electronic communication” and “financial means” as modes of committing the offense. This broadens the scope to cover cyber-dissent and terror financing.

- New Terminology: The section introduces terms like “secession,” “armed rebellion,” and “subversive activities.”

Comparative Analysis: Section 124A IPC vs Section 152 BNS

To understand the practical implications, let us compare the two provisions directly:

| Feature | Section 124A (IPC) | Section 152 (BNS) |

|---|---|---|

| Name of Offense | Sedition | Acts endangering sovereignty, unity, and integrity |

| Protected Entity | Government established by law | Sovereignty, Unity, and Integrity of India |

| Key Action Words | Hatred, Contempt, Disaffection | Secession, Armed Rebellion, Subversive Activities, Separatist Activities |

| Mens Rea | Implied (often debated) | Explicit (“Purposely or knowingly”) |

| Mediums | Words, signs, visible representation | Adds Electronic communication & Financial means |

| Punishment | Life imprisonment or up to 3 years | Life imprisonment or up to 7 years |

Critical Observation: The punishment gap has been closed. Under the IPC, judges had discretion between a lenient 3 years or a harsh life term. The BNS removes the 3-year option, setting the lower ceiling at 7 years, indicating a legislative intent to treat these offenses more severely.

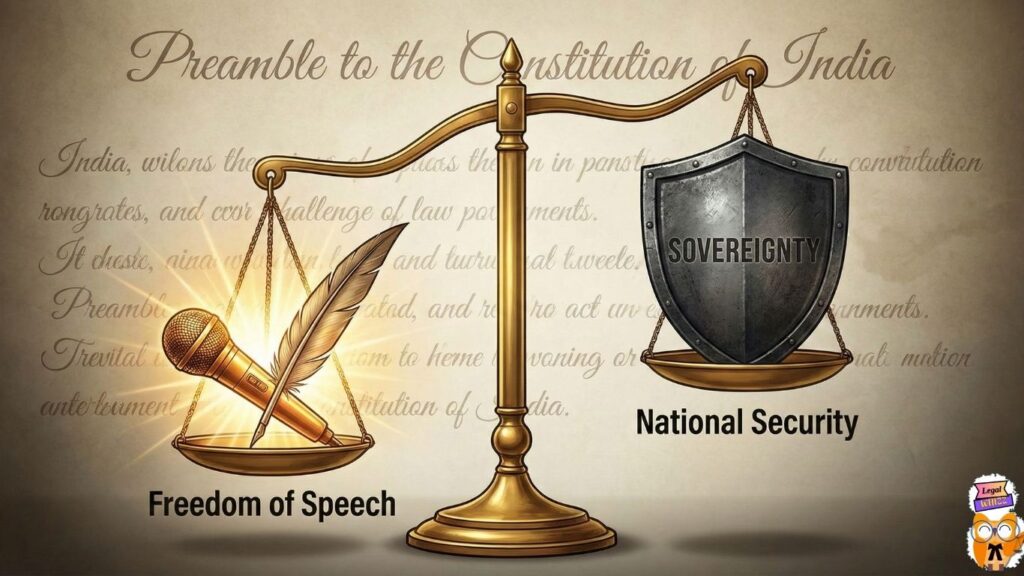

The Constitutional Conflict: Free Speech vs. National Security

The debate around sedition has always been a tug-of-war between Article 19(1)(a) (Freedom of Speech and Expression) and Article 19(2) (Reasonable Restrictions).

The Kedar Nath Singh Precedent (1962)

In the landmark case of Kedar Nath Singh v. State of Bihar, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of Section 124A but read it down. The Court held that mere criticism of the government is not sedition. For an act to be seditious, it must have a “pernicious tendency” to create public disorder or incite violence.

The 2022 Supreme Court Stay

In May 2022, in S.G. Vombatkere v. Union of India, the Supreme Court took a historic step by keeping Section 124A in abeyance (suspension). The Court urged the Centre to reconsider the provision. The introduction of the BNS is the government’s response to this judicial nudge.

Does Section 152 BNS Pass the Constitutional Test?

While Section 152 removes the “disaffection against government” clause (which was the main friction point with free speech), it introduces “subversive activities.” Legal scholars argue that “subversive” is not defined in the BNS.

- The Concern: Without a precise definition, “subversive activities” could be interpreted broadly to include non-violent civil disobedience or intense political dissent, potentially violating the standard of “reasonable restriction.”

Is the New Law a “Repackaged” Sedition?

This is the central question facing legal experts today. Let’s analyze the arguments.

Argument: It is a Reform (The “Sovereignty” View)

Proponents argue that Section 152 is a necessary evolution.

- De-colonialization: Removing the word “sedition” and shifting focus from the “Government” (a colonial master concept) to the “Nation” aligns with democratic values.

- Specificity: Terms like “secession” and “armed rebellion” are more specific than the vague “disaffection.”

- Terrorism Link: By including financial and electronic means, the law effectively targets modern threats like cyber-terrorism and funded separatism.

Argument: It is Draconian (The “Free Speech” View)

Critics, however, argue that the law is “old wine in a new bottle”—and the new bottle is stronger.

- Vague Terminology: The phrase “encourages feelings of separatist activities” is dangerously ambiguous. Could advocating for a separate state within the Union (a constitutional right) be criminalized?

- Subversive Activities: This undefined term allows executive discretion. Is a labor strike “subversive”? Is an investigative report exposing state failure “subversive”?

- Harsher Sentences: Increasing the minimum maximum sentence from 3 years to 7 years suggests a more punitive approach.

Landmark Case Laws: Guiding Principles

Even though 124A is repealed, the jurisprudence established by Indian courts will likely guide the interpretation of Section 152 BNS.

- Queen-Empress v. Jogendra Chandra Bose (1891): Established the distinction between “disapprobation” (legitimate criticism) and “disaffection” (contrary to affection).

- Bal Gangadhar Tilak Case (1908): Highlighted how the state uses sedition to silence political rivals.

- Balwant Singh v. State of Punjab (1995): The Supreme Court ruled that the mere raising of slogans (e.g., “Khalistan Zindabad”) without any overt act or violence does not amount to sedition. This precedent is crucial for interpreting “separatist activities” under BNS.

- Vinod Dua v. Union of India (2021): The Court reaffirmed that journalists are protected from sedition charges for criticizing government handling of crises (like COVID-19) unless they incite violence.

Do read OTT Platforms and Cyber Law: Regulating Content vs. Freedom of Speech in India.

Conclusion: A New Chapter or a Recurred Verse?

The enactment of Section 152 BNS is undeniably a milestone. It formally buries the colonial term “sedition,” acknowledging that a free people cannot be “seditious” against a government they elected. The shift from protecting the “Government” to protecting “India” is legally sound and constitutionally preferable.

However, the devil lies in the details—specifically in the definition of “subversive activities” and “separatist feelings.” If these terms are interpreted broadly by law enforcement, the chilling effect on free speech could mirror, or even exceed, that of Section 124A.

As India moves forward, the judiciary will once again be called upon to define the boundaries. The true test of Section 152 will not be in its text, but in its application. Will it shield the nation from breaking apart, or will it be used to silence those who speak up? The answer will define the future of civil liberties in the world’s largest democracy.

Key Takeaways

- Sedition Removed: The word “Sedition” is absent in the new Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS).

- New Offense: Section 152 punishes acts endangering “sovereignty, unity, and integrity.”

- Focus Shift: Protection has shifted from the “Government” to the “Nation.”

- Modernized: Includes “electronic communication” and “financial means” as methods of offense.

- Punishment: The “3-year” imprisonment option is removed; punishment is now life or up to 7 years.

- Ambiguity: Terms like “subversive activities” remain undefined, raising concerns for free speech.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Is Sedition completely abolished in India? Technically, the term “sedition” is abolished. However, the offense has been reintroduced as Section 152 BNS, covering acts that endanger sovereignty and unity, with broader provisions for electronic and financial crimes.

Q2: What is the punishment under the new Section 152 BNS? The punishment is imprisonment for life or imprisonment which may extend to seven years, along with a fine.

Q3: Can I criticize the government under the new law? Yes. The explanation to Section 152 explicitly states that comments expressing disapprobation of government measures to obtain their alteration by lawful means are not an offense, provided they do not incite secession or armed rebellion.

Q4: How does Section 152 affect online posts? Section 152 explicitly includes “electronic communication.” This means social media posts, blogs, or messages that act to incite secession or subversive activities can lead to prosecution under this section.

My99exchbet? Claiming it as ‘mine’, are we? I’m intrigued. Gotta check if it lives up to the boast! Anyone already claimed it as *their* favourite? Worth going in? Access: my99exchbet